Andy Warhol Soup Cans Andy Warhol Soup Cans Pop Art

| Campbell's Soup Cans | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Andy Warhol |

| Year | 1962 |

| Medium | Constructed polymer paint on canvas |

| Dimensions | 20 past xvi inches (51 cm × 41 cm) each for 32 canvases |

| Location | Museum of Modern Fine art. Acquired through the Lillie P. Elation Bequest, New York (32 canvas series displayed by twelvemonth of introduction) |

| Accession | 476.1996.1–32 |

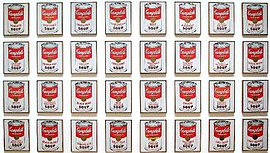

Campbell'south Soup Cans [1] (sometimes referred to every bit 32 Campbell'south Soup Cans )[2] is a work of fine art produced between Nov 1961 and March or Apr 1962[3] by American creative person Andy Warhol. It consists of thirty-two canvases, each measuring 20 inches (51 cm) in superlative × xvi inches (41 cm) in width and each consisting of a painting of a Campbell's Soup can—one of each of the canned soup varieties the company offered at the time.[i] The non-painterly works were produced by a screen printing process and depict imagery deriving from popular civilization and belong to the pop art movement.

Warhol was a commercial illustrator before embarking on painting. Campbell'south Soup Cans was shown on July 9, 1962, in Warhol's first one-human gallery exhibition[iv] [5] in the Ferus Gallery of Los Angeles, California curated by Irving Blum. The exhibition marked the W Coast debut of pop art.[6] The subject matter initially caused law-breaking, in role for its barb to the technique and philosophy of the before art motion of abstract expressionism. Warhol's motives as an artist were questioned. Warhol's clan with the subject led to his name condign synonymous with the Campbell's Soup Tin paintings.

Warhol produced a wide variety of art works depicting Campbell's Soup cans during iii distinct phases of his career, and he produced other works using a diverseness of images from the earth of commerce and mass media. Today, the Campbell'due south Soup cans theme is mostly used in reference to the original set up of paintings too every bit the later Warhol drawings and paintings depicting Campbell's Soup cans. Considering of the eventual popularity of the entire series of similarly themed works, Warhol's reputation grew to the betoken where he was not but the nigh-renowned American popular art artist,[7] but also the highest-priced living American artist.[8]

Early career [edit]

| External video | |

|---|---|

| |

New York art scene [edit]

Warhol arrived in New York City in 1949, directly from the School of Fine Arts at Carnegie Establish of Technology.[10] He speedily achieved success as a commercial illustrator, and his first published drawing appeared in the Summertime 1949 issue of Glamour Magazine.[11] In 1952, he had his first art gallery show at the Bodley Gallery with a brandish of Truman Capote-inspired works.[12] By 1955, he was tracing photographs borrowed from the New York Public Library's photo collection with the hired assistance of Nathan Gluck, and reproducing them with a process he had developed earlier as a collegian at Carnegie Tech. His process, which foreshadowed his later piece of work, involved pressing moisture ink illustrations against adjoining paper.[13] During the 1950s, he had regular showings of his drawings, and exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art (Contempo Drawings, 1956).[10]

Pop art [edit]

In 1960, Warhol began producing his starting time canvases, which he based on comic strip subjects.[14] In tardily 1961, he learned the process of silkscreening from Floriano Vecchi,[15] who had run the Tiber Press since 1953. Though the process generally begins with a stencil drawing, it often evolves from a diddled-upward photograph which is and then transferred with glue onto silk. In either instance, i needs to produce a glue-based version of a positive two-dimensional image (positive means the open spaces that are left are where the paint will appear). Usually, the ink is rolled across the medium so that it passes through the silk and not the glue.[sixteen] Campbell'due south Soup cans were among Warhol's showtime silkscreen productions; the first were U.Due south. dollar bills. The pieces were made from stencils; one for each color. Warhol did not brainstorm to convert photographs to silkscreens until after the original serial of Campbell'south Soup cans had been produced.[17]

Campbell's Soup Tin (Tomato), 1962. Stencils such as this are the ground for silkscreening.

Although Warhol had produced silkscreens of comic strips and of other popular fine art subjects, he supposedly relegated himself to soup cans as a subject at the time to avert competing with the more finished style of comics by Roy Lichtenstein.[18] He once said "I've got to do something that actually will accept a lot of impacts that volition be unlike enough from Lichtenstein and James Rosenquist, that will exist very personal, that won't await like I'm doing exactly what they're doing."[fifteen] Between November 1961 and March or April 1962, he produced the gear up of soup cans.[3] In February 1962, Lichtenstein displayed at a sold-out exhibition of cartoon pictures at Leo Castelli's eponymous Leo Castelli Gallery, ending the possibility of Warhol exhibiting his own drawing paintings.[19] Castelli had visited Warhol's gallery in 1961 and said that the work he saw at that place was likewise similar to Lichtenstein's,[20] [21] although Warhol's and Lichtenstein'south comic artwork differed in subject field and techniques (e.thousand., Warhol's comic-strip figures were humorous pop-culture caricatures such as Popeye, while Lichtenstein's were generally of stereotypical hero and heroines, inspired by comic strips devoted to adventure and romance).[22] Castelli chose non to represent both artists at that fourth dimension. (He would, in Nov 1964, be exhibiting Warhol, his Bloom Paintings, then again Warhol in 1966.[23]) Lichtenstein's 1962 show was quickly followed by Wayne Thiebaud'southward April 17, 1962, 1-human show at the Allan Stone Gallery featuring all-American foods, which agitated Warhol as he felt it jeopardized his own food-related soup can works.[24] Warhol was considering returning to the Bodley gallery, but Bodley's manager did non like his pop artworks.[15] In 1961, Warhol was offered a three-man show past Allan Stone at the latter'southward xviii East 82nd Street Gallery with Rosenquist and Robert Indiana, only all iii were insulted by this proffer.[25]

Irving Blum was the kickoff dealer to prove Warhol's soup can paintings.[four] Blum happened to be visiting Warhol in December 1961[26] so May 1962, at a fourth dimension when Warhol was being featured in a May eleven, 1962 Time mag article "The Slice-of-Cake School" [27] (that included a portion of Warhol'southward silkscreened 200 1 Dollar Bills), along with Lichtenstein, Rosenquist, and Wayne Thiebaud.[28] Warhol was the but artist whose photograph actually appeared in the article, which is indicative of his knack for manipulating the mass media.[29] Blum saw dozens of Campbell's Soup can variations, including a grid of Ane-Hundred Soup Cans that day.[18] Blum was shocked that Warhol had no gallery organisation and offered him a July show at the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles. This would be Warhol's first one-human being show of his pop art.[4] [five] Warhol was assured by Blum that the newly founded Artforum magazine, which had an role above the gallery, would cover the evidence. Not merely was the prove Warhol's first solo gallery exhibit, just it was considered to exist the Due west Coast premiere of popular art.[vi] A letter from Blum to Warhol dated June ix, 1962, set the exhibition opening for July nine.[30] Andy Warhol's first New York solo Popular showroom was hosted at Eleanor Ward's Stable Gallery November 6–24, 1962. The exhibit included the works Marilyn Diptych, Greenish Coca-Cola Bottles, and Campbell'due south Soup Cans.[31]

The premiere [edit]

Black font coloring is visible in Clam Chowder and Beef canvases from Campbell'southward Soup Cans, 1962.

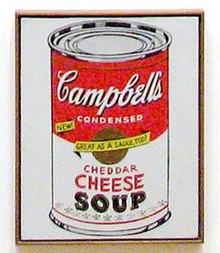

Gilded banners make the Cheddar Cheese canvass from Campbell's Soup Cans, 1962 unique.

Warhol sent Blum xxx-two xx-by-16-inch (510 mm × 410 mm) canvases of Campbell's Soup tin can portraits, each representing a particular diversity of the Campbell'south Soup flavors available at the time.[1] A postcard dated June 26, 1962 sent by from Irving Blum states " 32 ptgs arrived safely and wait beautiful. strongly advise maintaining a low price level during initial exposure here".[3] The thirty-two canvases are very similar: each is a realistic depiction of the iconic, mostly red and white Campbell's Soup can silkscreened onto a white background. The canvases take minor variation in the lettering of the multifariousness names. Virtually of the letterings are painted in reddish letters. Iv varieties have blackness lettering: Clam Chowder has parenthetical black lettering below the diverseness proper noun that said (Manhattan Style), which means that the soup is tomato- and broth-based instead of the cream-based New England style; Beefiness has parenthetical blackness lettering beneath the variety name that says (With Vegetables and Barley); Scotch Broth has parenthetical blackness lettering below the variety proper noun that said (A Hearty Soup); and Minestrone had black parenthetical lettering proverb (Italian-Manner Vegetable Soup). In that location are ii varieties with red lettered parenthetical labels: Beef Goop (Bouillon) and Consommé (Beefiness). The font sizes only vary slightly in the variety names. However, there are a few notable stylistic font differences. Old-fashioned Tomato Rice is the merely variety with lower case script. This lower example script appears to be from a slightly different font than the other variety name messages. There are other stylistic differences. Sometime-fashioned Tomato Rice has the discussion Soup depicted lower on the tin, in identify of a portion of ornamental starlike symbols at the bottom that the other 31 varieties have. As well, Cheddar Cheese has two banner-like addenda. In the center-left, a small aureate banner says "New!", and a middle center golden banner says "Great Every bit A Sauce Too!".

The exhibition opened on July 9, 1962, with Warhol absent-minded. The thirty-two unmarried soup can canvases were placed in a single line, much like products on shelves, each displayed on narrow individual ledges.[32] The contemporary impact was uneventful, only the historical impact is considered today to have been a watershed. The gallery audience was unsure what to make of the exhibit. A John Coplans Artforum article, which was in part spurred on by the responding display of dozens of soup cans by a nearby gallery with a display advert them at three for 60 cents, encouraged people to accept a stand on Warhol.[33] [34] Few really saw the paintings at the Los Angeles showroom or at Warhol's studio, only word spread in the form of controversy and scandal due to the work's seeming attempt to replicate the appearance of manufactured objects.[35] Extended debate on the merits and ethics of focusing 1'due south efforts on such a mundane commercial inanimate model kept Warhol'southward work in art world conversations. The pundits could non believe an artist would reduce the art form to the equivalent of a trip to the local grocery shop. Talk did not translate into monetary success for Warhol. Dennis Hopper was the beginning of only a 6 to pay $100 for a canvas. Blum decided to try to go along the thirty-two canvases as an intact ready and bought dorsum the few sales. This pleased Warhol who had conceived of them equally a set, and he agreed to sell the set for ten monthly $100 installments to Blum.[17] [33] Warhol had passed the milestone of his first serious art show. While this exhibition was on view in Los Angeles, Martha Jackson canceled another planned December 1962 New York exhibition.[36]

The Ferus testify closed on August 4, 1962, the day before Marilyn Monroe'due south death. Warhol went on to purchase a Monroe publicity still from the flick Niagara, which he later cropped and used to create one of his most well-known works: his painting of Marilyn. Although Warhol continued painting other pop art, including Martinson'due south coffee cans, Coca-Cola bottles, S&H Green Stamps, and Campbell's Soup cans, he before long became known to many as the artist who painted celebrities. He returned to Blum'south gallery to exhibit Elvis and Liz in October 1963.[iv] His fans Dennis Hopper and Brooke Hayward (Hopper'south married woman at the time) held a welcoming party for the event.[37]

Since Warhol gave no indication of a definitive ordering of the drove, the sequence chosen past MoMA (in the flick at the upper right of this commodity) in the display from their permanent collection reflects the chronological guild in which the varieties were introduced by the Campbell Soup Company, beginning with Tomato in the upper left, which debuted in 1897.[i] Past April 2011, the curators at the MoMA had reordered the varieties, moving Clam Chowder to the upper left and Tomato to the bottom of the four rows.[1]

Motivation [edit]

100 Cans, 1962. Example of the variations that Irving Blum saw when determining to introduce him by exhibit. Currently in the collection of the Albright–Knox Art Gallery.

Several anecdotal stories supposedly explain why Warhol chose Campbell's Soup cans as the focal betoken of his pop art. Ane reason is that he needed a new subject area subsequently he abased comic strips, a movement taken in part due to his respect for the refined piece of work of Roy Lichtenstein. According to Ted Carey—one of Warhol's commercial art assistants in the tardily 1950s—it was Muriel Latow who suggested the idea for both the soup cans and Warhol'due south early U.S. dollar paintings.[30]

Muriel Latow was so an aspiring interior decorator, and owner of the Latow Art Gallery in the East 60s in Manhattan. She told Warhol that he should paint "Something you run into every twenty-four hour period and something that everybody would recognize. Something similar a can of Campbell'southward Soup." Ted Carey, who was in that location at the time, said that Warhol responded past exclaiming: "Oh that sounds fabled." A $l bank check dated Nov 23, 1961 in the archive of the Andy Warhol Museum confirms the story.[26] Co-ordinate to Carey, Warhol went to a supermarket the following day and bought a case of "all the soups", which Carey said he saw when he stopped by Warhol'due south apartment the next day. When the art critic Thousand. R. Swenson asked Warhol in 1963 why he painted soup cans, the artist replied, "I used to potable information technology, I used to have the aforementioned lunch every day, for xx years."[30] [38]

Another account of Latow'southward influence on Warhol holds that she asked him what he loved most, and because he replied "coin" she suggested that he paint U.S. dollar bills.[39] Co-ordinate to this story, Latow later on brash that in addition to painting money he should paint something else very simple, such equally Campbell's Soup cans.

In an interview for London'due south The Face in 1985, David Yarritu asked Warhol about flowers that Warhol's mother made from tin cans. In his response, Warhol mentioned them as 1 of the reasons behind his first tin tin paintings:

- David Yarritu: I heard that your mother used to make these fiddling tin flowers and sell them to help back up you lot in the early days.

- Andy Warhol: Oh God, yes, it'due south truthful, the tin flowers were made out of those fruit cans, that's the reason why I did my get-go tin-tin paintings ... Yous take a tin can-can, the bigger the tin-can the better, like the family size ones that peach halves come in, and I recollect you cut them with scissors. Information technology's very piece of cake and you lot only make flowers out of them. My mother always had lots of cans around, including the soup cans.[30]

Several stories mention that Warhol'southward choice of soup cans reflected his own avid devotion to Campbell's soup every bit a consumer. Robert Indiana once said: "I knew Andy very well. The reason he painted soup cans is that he liked soup."[xl] He was thought to take focused on them because they equanimous a daily dietary staple.[41] Others observed that Warhol simply painted things he held shut at heart. He enjoyed eating Campbell'southward soup, had a gustation for Coca-Cola, loved money, and admired moving-picture show stars. Thus, they all became subjects of his work. Yet another account says that his daily lunches in his studio consisted of Campbell'due south Soup and Coca-Cola, and thus, his inspiration came from seeing the empty cans and bottles accrue on his desk-bound.[42]

Warhol did non choose the cans because of concern relationships with the Campbell Soup Company. Even though the visitor at the time sold 4 out of every 5 cans of prepared soup in the U.s., Warhol preferred that the company not exist involved "because the whole point would be lost with whatsoever kind of commercial tie-in."[43] However, by 1965, the company knew him well enough that he was able to coax actual can labels from them to use equally invitations for an exhibit.[44] They even commissioned a sheet.[45]

Bulletin [edit]

Warhol had a positive view of ordinary culture and felt the abstract expressionists had taken great pains to ignore the splendor of modernity.[7] The Campbell's Soup Tin can series, along with his other series, provided him with a chance to express his positive view of mod culture. Nevertheless, his deadpan manner endeavored to be devoid of emotional and social commentary.[7] [46] The work was intended to exist without personality or individual expression.[47] [48] Warhol'southward view is encapsulated[29] in the Time magazine description of the 'Slice of Cake School,' that "... a group of painters have come to the common conclusion that the most banal and even vulgar trappings of modern culture can, when transposed to sail, go Fine art."[27]

His pop art work differed from serial works past artists such as Monet, who used series to represent discriminating perception and show that a painter could recreate shifts in fourth dimension, light, flavor, and weather with hand and eye. Warhol is now understood to represent the modern era of commercialization and indiscriminate "sameness." When Warhol eventually showed variation it was non "realistic." His subsequently variations in color were almost a mockery of discriminating perception. His adoption of the pseudo-industrial silkscreen process spoke against the use of a serial to demonstrate subtlety. Warhol sought to refuse invention and nuance by creating the advent that his work had been printed,[47] and he systematically recreated imperfections.[39] His series work helped him escape Lichtenstein'south lengthening shadow.[49] Although his soup cans were non every bit shocking and vulgar equally some of his other early pop art, they still offended the fine art world'due south sensibilities that had developed so as to partake in the intimate emotions of artistic expression.[47]

Contrasting against Caravaggio'southward sensual baskets of fruit, Chardin's plush peaches, or Cézanne'due south vibrant arrangements of apples, the mundane Campbell'southward Soup Cans gave the art earth a chill. Furthermore, the thought of isolating eminently recognizable pop civilization items was ridiculous enough to the art world that both the merits and ideals of the work were perfectly reasonable debate topics for those who had not even seen the piece.[50] Warhol's pop art can be seen as a relation to Minimal art in the sense that it attempts to portray objects in their near simple, immediately recognizable class. Pop fine art eliminates overtones and undertones that would otherwise be associated with representations.[51]

Warhol conspicuously changed the concept of art appreciation. Instead of harmonious 3-dimensional arrangements of objects, he chose mechanical derivatives of commercial analogy with an emphasis on the packaging.[43] His variations of multiple soup cans, for example, made the process of repetition an appreciated technique: "If you lot take a Campbell's Soup can and repeat it fifty times, you are not interested in the retinal image. According to Marcel Duchamp, what interests you is the concept that wants to put fifty Campbell's Soup cans on a sheet."[52] The regimented multiple tin depictions almost become an abstraction whose details are less important than the panorama.[53] In a sense, the representation was more than of import than that which was represented.[51] Warhol's interest in machinelike creation during his early pop art days was misunderstood by those in the art world, whose value system was threatened by mechanization.[54]

In Europe, audiences had a very different take on his work. Many perceived information technology as a subversive and Marxist satire on American capitalism.[43] If not subversive, information technology was at least considered a Marxist critique of popular culture.[55] Given Warhol's apolitical outlook in general this is non likely the intended message. According to writer David Bourdon, his pop art may accept been cipher more than an attempt to attract attention to his work.[43]

Variations [edit]

Small Torn Campbell's Soup Tin can (Pepper Pot), 1962. In May 2006 the painting sold for $11.viii one thousand thousand.[ citation needed ]

Warhol followed the success of his original series with several related works incorporating the aforementioned theme of Campbell's Soup cans subjects. These subsequent works along with the original are collectively referred to every bit the Campbell's Soup cans series and often only equally the Campbell's Soup cans. The subsequent Campbell's Soup can works were very diverse. The heights ranged from 20 inches (510 mm) to six anxiety (1.eight thou).[56] Occasionally, he chose to depict cans with torn labels, peeling labels, crushed bodies, or opened lids (images right).

Irving Blum made the original thirty-two canvases available to the public through an organization with the National Gallery of Fine art in Washington, DC past placing them on permanent loan 2 days before Warhol's death.[39] [57] However, the original Campbell's Soup Cans is now a part of the Museum of Modern Fine art permanent collection.[1] A impress called Campbell'south Soup Cans II is part of the permanent collection of the Museum of Contemporary Fine art in Chicago. 200 Campbell's Soup Cans, 1962 (Acrylic on sheet, 72 inches 10 100 inches), in the private collection of John and Kimiko Powers is the largest single canvas of the Campbell'due south Soup tin paintings. It is equanimous of ten rows and twenty columns of numerous flavors of soups. Experts point to it as one of the most significant works of pop art both as a pop representation and every bit conjunction with immediate predecessors such equally Jasper Johns and the successors movements of Minimal and Conceptual art.[58] The very like 100 Cans from the Albright-Knox Fine art Gallery collection is shown in a higher place. The earliest soup can painting seems to be Campbell'due south Soup Can (Tomato Rice), a 1961 ink, tempera, crayon, and oil sail.[59]

In many of the works, including the original series, Warhol drastically simplified the gilded medallion that appears on Campbell's Soup cans by replacing the paired emblematic figures with a flat xanthous deejay.[43] In most variations, the only hint of 3-dimensionality came from the shading on the tin lid. Otherwise the image was apartment. The works with torn labels are perceived as metaphors of life in the sense that even packaged food must meet its finish. They are oftentimes described equally expressionistic.[60]

By 1970, Warhol established the record auction price for a painting by a living American artist with a $60,000 auction of Big Campbell'southward Soup Can with Torn Label (Vegetable Beefiness) (1962) in a sale at Parke-Bernet, the preeminent American auction house of the day (later caused by Sotheby'southward).[eight] This record was cleaved a few months later past his rival for the artworld's attention and approval, Lichtenstein, who sold a delineation of a behemothic brush stroke, Big Painting No. 6 (1965) for $75,000.[61]

In May 2006, Warhol's Small Torn Campbell Soup Tin can (Pepper Pot) (1962) sold for $xi,776,000 and set the electric current auction earth tape for a painting from the Campbell Soup Can series.[62] [63] The painting was purchased for the collection of Eli Broad,[64] a human being who once fix the record for the largest credit card transaction when he purchased Lichtenstein's "I ... I'm Distressing" for $2.5 million with an American Express carte du jour.[65] The $11.8 million Warhol sale was part of the Christie's Sales of Impressionist, Modern, Post-War and Contemporary Fine art for the Spring Season of 2006 that totaled $438,768,924.[ commendation needed ]

The broad diversity of work produced using a semi-mechanized procedure with many collaborators, Warhol's popularity, the value of his works, and the diversity of works beyond various media and genre have created a need for the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Lath to certify the authenticity of works by Warhol.[66]

On April 7, 2016, 7 Campbell'due south Soup Cans prints were stolen from the Springfield Fine art Museum. The FBI announced a $25,000 reward for data nearly the stolen art pieces.[67]

Decision [edit]

Example of varied coloring

Warhol'southward production of Campbell's Soup can works underwent three distinct phases. The first took place in 1962, during which he created realistic images, and produced numerous pencil drawings of the field of study.[49] In 1965, Warhol revisited the theme while arbitrarily replacing the original red and white colors with a wider diversity of hues. In the late 1970s, he once more returned to the soup cans while inverting and reversing the images.[59] The all-time-remembered Warhol Campbell's Soup can works are from the first stage. Warhol is further regarded for his iconic series celebrity silkscreens of such people equally Elvis Presley, Marilyn Monroe and Liz Taylor, produced during his 1962–1964 silkscreening phase. His most unremarkably repeated painting subjects are Taylor, Monroe, Presley, Jackie Kennedy and similar celebrities.[68]

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b c d eastward f "The Collection". The Museum of Modern Fine art. 2007. Retrieved March 9, 2007.

- ^ Frazier, p. 708.

- ^ a b c Popular, The Genius of Andy Warhol. Harper Collins. 2009. pp. 118. ISBN9780066212432.

- ^ a b c d Angell, p. 38.

- ^ a b Livingstone, p. 32.

- ^ a b Lippard, p. 158.

- ^ a b c Stokstad, p. 1130.

- ^ a b Bourdon p. 307.

- ^ "Why is this Art? Warhol'southward Campbell'due south Soup Cans". Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Retrieved Dec 21, 2012.

- ^ a b Livingstone, p. 31.

- ^ Watson, p. 25.

- ^ Watson, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Watson, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Harrison and Wood, p. 730.

- ^ a b c Watson, p. 79.

- ^ Warhol and Hackett, p. 28.

- ^ a b Bourdon, p. 123.

- ^ a b Bourdon, p. 109.

- ^ Bourdon, p. 102.

- ^ Watson, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Angell, p. 84.

- ^ Angell, p. 86.

- ^ Sylvester, p. 386.

- ^ Bourdon, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Bourdon, p. 100.

- ^ a b The Genius of Andy Warhol Pop. Harper Collins. 2009. pp. 87. ISBN978006621243-2.

- ^ a b "The Slice-of-Block School". Time. 79 (19): 52. May 11, 1962. Retrieved December 25, 2013.

- ^ Watson p. 79–80.

- ^ a b Bourdon, p. 110.

- ^ a b c d Comenas, Gary. "Warholstars: The Origin of the Soup Cans". warholstars.org. Retrieved January 4, 2007.

- ^ "Andy Warhol Chronology". warholstars.org. Retrieved Nov viii, 2008.

- ^ Archer, p. 14.

- ^ a b Watson p. fourscore.

- ^ Bourdon, p. 120.

- ^ Bourdon, p. 87.

- ^ Watson pp. 80–81.

- ^ Angell, p. 101.

- ^ Harrison and Woods, p. 732. Republished from Swenson, G. R., "What is Pop Art? Interviews with Eight Painters (Part I)," ARTnews, New York, November 7, 1963, reprinted in John Russell and Suzi Gabik (eds.), Pop Art Redefined, London, 1969, pp. 116–119.

- ^ a b c Marcade p. 28.

- ^ Comenas, Gary (December 1, 2002). "Warholstars". New York Times . Retrieved Dec 17, 2006.

- ^ Faerna, p. 20.

- ^ Baal-Teshuva, p. 18.

- ^ a b c d e Bourdon, p. 90.

- ^ Warhol and Hackett p. 163.

- ^ Bourdon, p. 213.

- ^ Random Firm Library of Painting and Sculpture Volume 4, p. 187.

- ^ a b c Warin, Vol 32, p. 862.

- ^ Vaughan, Vol 5., p. 82.

- ^ a b Bourdon, p. 96.

- ^ Bourdon, p. 88.

- ^ a b Lucie-Smith, p. x.

- ^ Constable, Rosalind, "New York's Avant Garde and How it Got In that location," New York Herald Tribune, May 17, 1964, p. 10. cited in Bourdon, p. 88.

- ^ Bourdon, pp. 92–96.

- ^ Lippard, p. x.

- ^ Livingstone, p. xvi.

- ^ Bourdon, p. 91.

- ^ Archer, p. 185.

- ^ Lucie-Smith, p. sixteen.

- ^ a b Bourdon p. 99.

- ^ Bourdon, p. 92.

- ^ Hahn, Susan (November 19, 1970). "Record Prices for Art Sale at New York Auction". Lowell Sun. p. 29. Retrieved May 12, 2012.

- ^ "Andy Warhol's Campbell Soup Sells For $11.7 One thousand thousand". ArtDaily. May 11, 2006. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ "Andy Warhol'southward Iconic Campbell's Soup Tin can Painting Sells for $xi.seven Million". Fob News. Associated Press. May 10, 2006. Archived from the original on November 14, 2007. Retrieved January 29, 2007.

- ^ AFP. (May 11, 2006). Auction sets record for Warhol's soup series. ABC News (Commonwealth of australia). Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- ^ "American Topics". International Herald Tribune. Jan 25, 1995. Archived from the original on Dec 9, 2006. Retrieved January 30, 2007.

- ^ "The Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board, Inc". Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. Archived from the original on January 17, 2008. Retrieved March nine, 2007.

- ^ "FBI Offers $25K Reward After Iconic Warhol Art Stolen". NBC News.

- ^ Sylvester, p. 384.

References [edit]

- Angell, Callie (2006). Andy Warhol Screen Tests: The Films of Andy Warhol Catalogue Raissonné. New York: Abrams Books in Association With The Whitney Museum of American Fine art. ISBN0-8109-5539-3.

- Archer, Michael (1997). Art Since 1960 . Thames and Hudson Ltd. ISBN0-500-20298-2.

- Baal-Teshuva, Jacob, ed. (2004). Andy Warhol: 1928–1987. Prutestel. ISBN3-7913-1277-four.

- Bourdon, David (1989). Warhol. Harry Due north. Abrams, Inc. Publishing. ISBN0-8109-2634-2.

- Faerna, Jose Maria, ed. (September 1997). Warhol. Henry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers. ISBN0-8109-4655-vi.

- Frazier, Nancy (2000). The Penguin Concise Dictionary of Fine art History. Penguin Group. ISBN0-670-10015-three.

- Harrison, Charles; Forest, Paul, eds. (1993). Art Theory 1900–1990: An Anthology of Changing Ideas. Blackwell Publishers. ISBN0-631-16575-four.

- Lippard, Lucy R. (1985) [1970]. Pop Art. Thames and Hudson. ISBN0-500-20052-1.

- Livingstone, Marco, ed. (1991). Pop Art: An International Perspective. London: The Royal University of Arts. ISBN0-8478-1475-0.

- Lucie-Smith, Edward (1995). Artoday . Phaidon. ISBN0-7148-3888-eight.

- Marcade, Bernard; De Vree, Freddy (1989). Andy Warhol. Galerie Isy Brachot.

- Random Firm Library of Painting and Sculpture Book 4, Dictionary of Artists and Art Terms . Random House. 1981. ISBN0-394-52131-v.

- Stokstad, Marilyn (1995). Art History . Prentice Hall, Inc., and Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers. ISBN0-8109-1960-5.

- Sylvester, David (1997). Well-nigh Modernistic Art: Disquisitional Essays 1948–1997. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN0-8050-4441-viii. (Citing "Factory to Warhouse", May 22, 1994, Independent on Sunday Review as principal source)

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Vaughan, William, ed. (2000). The Encyclopedia of Artists. Vol. v. Oxford University Press, Inc.

- Warin, Jean, ed. (2002) [1996]. The Dictionary of Art. Vol. 32. Macmillan Publishers Limited.

- Warhol, Andy & Hackett, Pat (1980). Popism: The Warhol Sixties. Harcourt Books. ISBN0-15-672960-one.

- Watson, Steven (2003). Manufacturing plant Made: Warhol and the Sixties. Pantheon Books.

External links [edit]

- Campbell's Soup Cans, 1962 – The Museum of Modern Art, New York

manningweenctiny1987.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Campbell%27s_Soup_Cans

0 Response to "Andy Warhol Soup Cans Andy Warhol Soup Cans Pop Art"

Postar um comentário